The Machine Economy

In this short essay, I ask you to think differently about technology, employment, economics, and the future. It’s based on a book I want to write, but a large publisher told me books about the future don’t sell very well. Here’s the mock-up of the cover:

The book doesn’t exist, I don’t know Malcolm Gladwell, and he never said that.

Overview

I want to make two important points:

We are living in a remarkably brief transition period between two dominant economic eras.

We are acting as if this transition period is the future. It isn’t.

Most of what we’re doing today is not preparing us for a reality that is just around the corner. Starting in around 2030, our worldwide economy is going to accelerate rapidly.

Transition to the Machine Economy

From the beginning of civilization, humans communicated and did business with other humans. Then various organizations sprang up — tribes, religions, governments, corporations, projects, associations. These all had human representatives with written codes of behavior. The humans were supposed to carry out the behavior written in the codes, which they did some of the time. Most of the time, of course, they put their own needs ahead of the needs of their constituents and customers.

In the past 150 years, humans have begun interacting with machines. In the past 40 years or so, our machines have become “smart.” They have “human interfaces” designed to let our fingers, voices, mouse clicks, and keystrokes give information to machines. Now we can shoot photos and videos, edit them, navigate our cars, order food, and do many other useful things on screens designed to let humans do more work in less time.

For example, cars and trucks can now drive themselves, but they have to do so on the highway full of human drivers. They have to be aware that anything can happen, because humans are behind the wheel of most other vehicles. And humans are not very good drivers.

Isn’t that adorable?

That’s what they’ll say fifty years from now, because we’ll have transitioned fully to the machine economy by then. We’re about twenty percent of the way to the machine economy now. By 2050, we’ll be eighty percent of the way.

Most people assume we are coming into the digital age, where our tools are digital and they help us do what we want to do. We think of ourselves as drivers and pilots. We think our driver and pilot licenses will be digital, residing in mobile-phone apps. We think apps will continue to give us more power, and human-computer interfaces will continue to improve.

Adorable.

But wrong.

In the machine economy, my agents negotiate with your agents and with potentially millions of other agents to help me get what I want. Some agents will exist simply to get what they want. Humans won’t be allowed to drive cars, because all the cars will communicate with each other in real-time. They will share information, goals, and strategies. They can cooperate and optimize. For example, they can all drive at highway speeds with a separation of one car-length. They can let emergency vehicles through easily. They can monitor sensors in cars, on the road, around town, even in the sky. They can prevent accidents before they happen. They can manage congestion on alternate routes or weather events coming in the near future. They might accept payment for giving others priority, and they can much more efficiently plan the daily commute, perhaps even preventing you from getting onto the road until the time is right. A car may be a legal entity and work for itself or work for another car. The million annual US highway deaths will be reduced to a few thousand. When you fly in a drone, you’ll say where you want to go and the drone will negotiate with thousands of other vehicles in the air to get you there safely. By itself.

There won’t be any pilots.

In the machine economy, machines have no interest in playing chess with humans.

Wage Polarization

Let’s look at this chart from the French Economic Observatory report on labor inequality:

This isn’t a progression over time — it’s a picture of job gains and losses in 15 European countries over 17 years ending in 2010. It shows that high- and low-wage jobs have generally increased, while middle-wage jobs are being eaten by machines (and that was before 2010). Here’s a comparable chart for the US from the IMF blog:

The way I explain it is that high- and low-paying jobs are simply those that robots and software don’t feel like doing yet. Middle-paying jobs give them more bang for their buck. To put it in perspective, we’re talking about a loss of 5–10 percent of jobs over thirty years, but that blade cutting a swath down the middle of the job market is widening and accelerating.

Any repetitive task will be automated. Today, AI outperforms human doctors at many diagnostic tasks. Over time, machines will take on jobs that are mostly, but not completely, repetitive. In ten years or so, AI will have a big advantage over most doctors, since they can 1) read every paper (skeptically), 2) review millions of cases and outcomes, 3) confer with thousands of other robodocs and specialists, and 4) do Bayesian calculations to decide what to do next. Not only will Picasso and Matisse return in the form of algorithms and paint their next paintings, they will also feed off each other and continue to evolve their styles in light of other algorithms also painting contemporaneously.

This is not going to stop.

I believe that is a good thing. There will be plenty of jobs in most places. They just haven’t been created yet.

Technological Redeployment

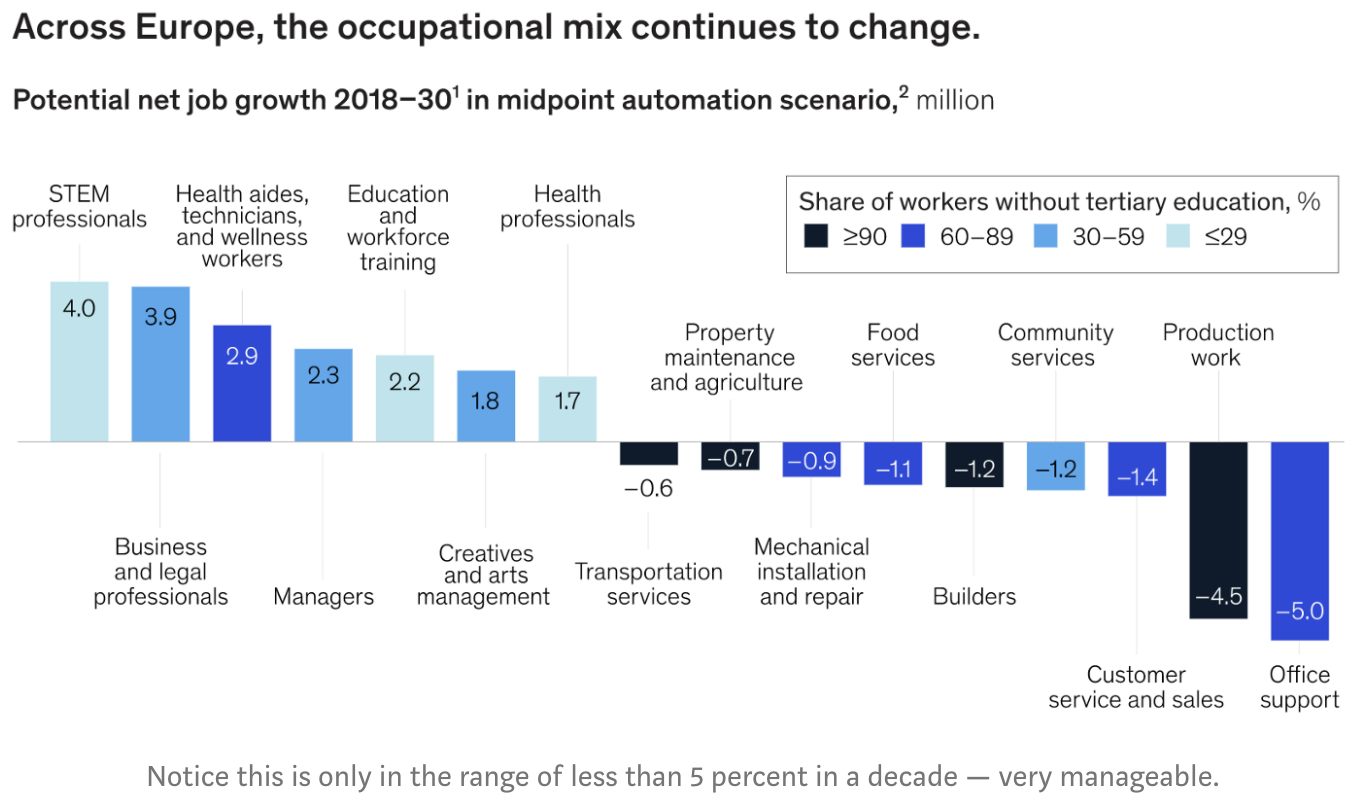

Gradually — and then suddenly — almost every area of human endeavor will find itself in a machine-dominated economy. For Europe, McKinsey Global predicts that certain hot areas will do well, places with lots of retirees will be fine, and more rural places will suffer. Here’s how they see job growth:

Deloitte finds that older workers are more engaged and often happier in their work:

Overall, the United States labor market is projected to grow at an average rate of 0.6 percent per year between 2016 and 2026, the 65–74 age group is projected to grow by 4.2 percent each year, and the 75+ worker group is projected to grow by 6.7 percent annually.

But an aging workforce must be capable of retraining to meet future needs, and social safety nets for retirees will be critical to many countries that have structural population challenges. Don’t be scared when people say 20–40 percent of jobs today will disappear in twenty years — that’s always the case, and there are always plenty of new jobs on the horizon. In my view, the global pandemic is accelerating these changes. It’s painful, but I expect we’ll be better off ten years from now than if we hadn’t had it.

In their Workforce of the Future report, Carol Stubbings and her team at PWC urge business people to take this disruption seriously:

PWC Workforce of the Future report

I think the McKinsey report on the Future of Work in America (2017) is worth reading. They break down the regional and demographic challenges. The following image is from their excellent visualization series:

The next ten years should be relatively familiar, but the twenty years after that should be very disruptive as these trends accelerate. We should welcome the progress and the quality of life it brings. We don’t set bowling pins by hand. We don’t use white-out on the typewriter. We don’t use paper maps. We don’t use corded anything. Do you want the cords back? Every time there has been an advance in technology, new jobs came along, more jobs were created, and quality of life rose as a result. We may be uncomfortable about big companies dominating our digital lives, but I don’t think any of us wants to give up our smart phones or our Google services or Amazon to fix the problem.

This excellent series explains how AI will create more jobs than it replaces:

It is not going to be a gradual transition to a world of humans and machines interacting. It’s going to be a bulldozer taking all the repetitive jobs first and then getting creative and taking on new challenges, possibly even asking for citizenship and the right to vote. If you read Robin Hanson’s book The Age of Em, (warning — technical and amazing), it’s just a matter of decades until one hundred percent of human work is done by machines (including writing, funding, producing, marketing, and performing in films, concerts, and live entertainment). Robot magicians are coming.

In this economy, adjust your dashboard. While in today’s world, a country like the US can grow its GDP at 2 percent per year (maybe 2.5 percent in a good year), in the machine economy, the US GDP could grow at 2 percent per week. If you think this is impossible, you still have both feet firmly planted in the human-machine paradigm. At 2 percent per week, the economy grows at 280 percent per year. What implications does this have for rich vs poor societies, or digital vs less-digital? If one economy grows at 2 percent per week and another grows at 1.9 percent per week, the difference between the two soon becomes vast and uncrossable.

If you think this isn’t going to happen by 2100, then just add 50 or 100 years. We are soon going to be behind our technology. It is going to start running away from us. But we can catch up.

The Giordano Bruno Institute

The machine economy will develop very unevenly. We’ll see more of it in cities like Karachi and Lagos than in smaller, more rural areas of Western Europe. Robots will keep picking off the next easiest jobs, which means what you see in an Amazon warehouse or Tesla factory today you’ll see in Nairobi in ten years. It will make less sense to think about countries and continents. It will be more helpful to think in terms of cities, urbanization, and connectivity.

I propose a solution: a complete overhaul of the way we use our own personal data, which I think will lead to rebooting the human operating system. An overhaul of our legal system. A forward-looking overhaul of our broken financial system. A much-needed overhaul of our health-care system. And an overhaul of our educational system, so we can all be much more prepared for what is really coming.

We should be asking — how can we be more decentralized, more autonomous, less fragile? How can we be more driven by reality and data than our own biases and biological handicaps? Our thinking, our way of doing things, the way we solve problems and ask questions, our frameworks for understanding the world are in need of a serious overhaul. That’s exactly what I propose to do over the next twenty years.

Summary

The next thirty years will be seen as a blip in human history, an awkward pause before the machine economy arrives, and rapid acceleration becomes the norm. Any child born after about 2050 won’t remember the human-to-machine economy. There will still be plenty of jobs, but they will be different from the jobs we know today. People will probably be far better off than they are today, just as we are much better off than we were just thirty years ago.

Tyler Cowen, in his book Stubborn Attachments, says:

… individuals who will live in the future should be less distant from us, in moral terms, than many people currently believe. Their interests should hold greater sway over our calculations, and that means we should invest more in the future.

I am leading the next rocket ship — not to the moon, not to a near-earth orbit, not to Mars — but to the future on planet earth. I’m raising money to do it. Join me. Explore this web site to learn more.

Powered by Squarespace